Making With / Researching With ⟶ Making With

Making With:

Conversations about Co-Creation

Lauren Hall and Matthew Reason

May 2023

Co-creation in the arts is broadly understood as engaging members of the public in the creative processes of making, devising, curating, presenting. Similarly, beyond the arts, co-creation and co-production describe the involvement of whoever a product or service is for in the development of that product or service. Examples might be transport users leading in the development of a new cooperative bus service; young people involved in designing a school’s uniform policy; patients consulting on the design of hospital waiting rooms. Beneath such broad understandings, however, things get more complex and the subtly different words used here – leading, designing, consulting – indicate various kinds of involvement. As Francois Matarasso asks, ‘what is the nature and degree of creative input people are actually being invited to contribute?’

Compass Live Art have a history of commissioning socially engaged, interactive live art in the public realm. They describe this as a model of co-creation, which is led by artists who collaborate with participants, whose contributions are incorporated as central elements of the projects as they develop. Compass were interested in exploring their model of co-creation further, aware that this was often contested territory, with implied hierarchies, expectations and understanding of what ‘better’ or ‘truer’ co-creation might entail.

We explored these questions with funding from the Centre for Cultural Value’s Collaborate Fund and through two strands. Elsewhere we explored participants’ journeys and their experiences of co-creation through a series of walking interviews. Here we examine the insights and discussions that emerged from a series of four dialogical workshops held with Compass commissioned artists past, present and future:

- Artists who had participated in previous Compass Live Art Festivals: Katie Etheridge, Simon Persighetti and Joshua Sofaer.

- Artists participating in the 2022 Compass Festival: Amy Lawrence, Toni Lewis, Silvia Mercuriali and Popeye Collective.

- Artists commissioned for future Compass Festivals: Rhiannon Armstrong, Alisa Oleva, Amy Pennington, Noam Youngrak Son and Ling Tan.

- Producers working for Compass Festival: Yasmin Goodison Braithwaite, Lydia Cottrell, Peter Reed and Alice Withers.

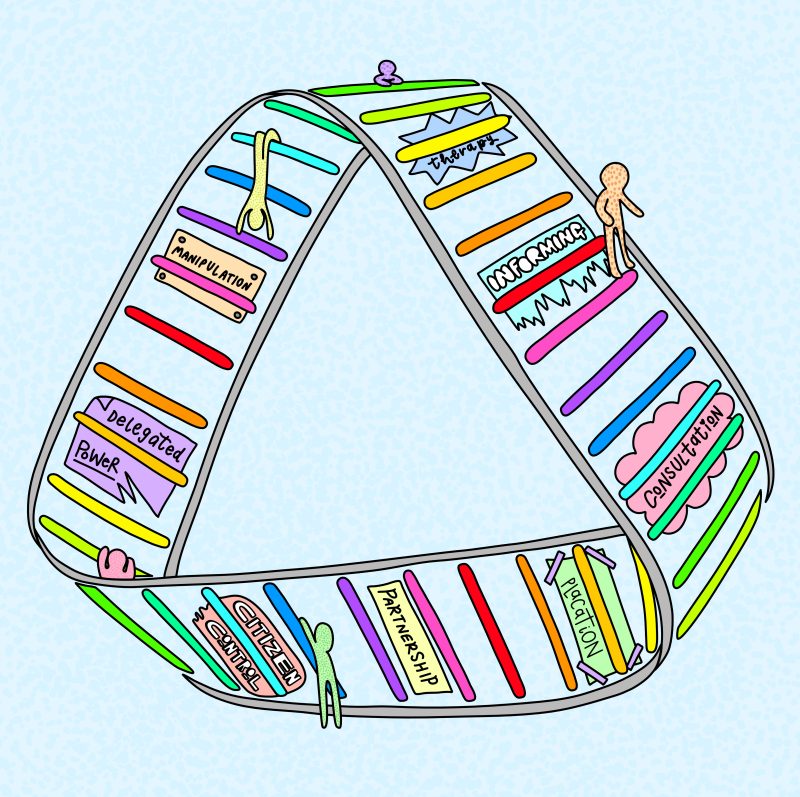

The purpose of the workshops was to put the participating artists and producers in conversation with each other about their practices and their insights about co-creation. We anticipated that the term would be very familiar to them, something with which they had already actively engaged and reflected. However, as a prompt and a shared starting point we circulated an image of Sherry Arnstein’s Ladder of Citizen Participation. First produced in 1969, this is a much discussed and critiqued visualisation of one model of public participation, but it is only one model and we were interested in how it might provoke thoughtful and productive conversation and the development of alternative models, frameworks and visualisations. Indeed, several of the artists responded by doodling over the ladder to create more intricate and less ridged relationships, while others proposed altogether different visual metaphors, which we have adopted here. Amongst our conclusions was a sense of the limitation of fixed or prescriptive definitions of co-creation, particularly ones that can overly determine artist processes or impose external hierarchical value judgement. This discussion works through our three representations of co-creation, presenting them as a fluid and responsive framework through which we can understand different relationships of making with.

Illustrations by Alyce Wood

Representation 1:

Co-creation as mobius ladder:

Everything everywhere all at once

Illustration by Alyce Wood

A ladder implies or even enforces a hierarchy, that it is better to be at the top than at the bottom. Indeed, the bottom three rungs of Arnstein’s ladder are labelled boldly ‘non-participation’. Rejection of this hierarchy was the single most recurring aspect of the dialogical workshops, although interestingly not necessarily in terms of rejecting the specific rungs on the ladder. Instead there was a recurring sense that not only did all position occur – even those with starkly negative connotations such as ‘manipulation’ or ‘placation’ – but that all were necessary at times, all were valuable in their own right. There was a sense that there was an implied pressure to move higher up the ladder, with ‘full’ co-creation seen as a ‘gold standard’; with this pressure variously described as coming from funders, internal reflections or from the logic of the ladder itself. However, there was resistance to this hierarchical progression. While the categories themselves were seen as useful, the hierarchy was not, as projects might occupy multiple points on the ladder at different times or even at the same time. These might vary according to the needs of the project or the interests and desires of the participants or audiences. While the ladder constructs an idea of discrete integers, the reality was often that multiple things were true at the same time.

As Amy Lawrence commented: ‘It’s multifaceted. And there isn’t one form of co-creation. I feel like many things can potentially be true at the same time.’

Several artists, including Amy, drew interconnected lines over the ladder of participation to illustrate the interconnectedness of the different rungs. As a visual metaphor we have adopted the mobius ladder, a never-ending loop that has neither up nor down, right side not wrong side. The rungs of the mobius ladder interlock and cannot be separated, things are not discrete but neither simply a random mess. There is a structure to the complexity of co-creation, but it is not linear.

Representation 2:

Co-creation as bouldering:

Problem solving

Illustration by Alyce Wood

As a principle, co-creation might seem ideologically driven – motivated by striving for ever more absolutely co-creative relationships. As discussed this is visually communicated by the ladder, with its implied hierarchical progression. In the workshops all the artists shared a strong political and social ethos behind engagement with co-creative processes, such as from Toni Lewis who discussed an interest in ‘horizontality’, in who has power and how that could be shared. There was also a recurring commitment to engaging with individuals and communities who might be minoritized or marginalised and providing space for their stories and collaboration. However, in practice decisions were as often driven by problem solving, rather than determined by a co-creative ethical purity. Several artists simply noted that when it came to co-creation, ‘it depends’ – on the needs of the project, on participants, on circumstances, on funding.

‘It depends’, however, does not mean a random process, but rather one informed by experience and vision. Amy Lawrence, for example, discussed co-creation as a deeply reflexive process: a ‘constant process of me questioning my own process’. In this manner rather than end points or outcomes, the positions on the ladder could be considered as methods, of ways of working and being with other people. Katie Etherridge commented: ‘It often starts with responding to context, so it’s definitely about people in place. A lot of listening, a lot of consultation, a huge amount of conversation, which is often the methodology that gets everything else going.’ There is a rigour to the processes of decision making, but also one of flexibility, adaptability, nuance.

In seeking to come up with an alternative visual metaphor to a hierarchical ladder, Joshua Sofaer proposed that of bouldering – the climbing discipline of finding technical and inventive solutions to ‘problems’:

You face the boulder, and sometimes you’re standing on the top, but you’re just kind of looking for whatever the next hold is, and you might be going up, you might be going down, but there’s not a sense of kind of an apex that you’re moving towards the top and that’s the, the desired place to be. The point is that you’re trying to find your way around it, you’re trying to navigate it, you’re trying to map it. […] I think that the arts practice itself is a bit like bouldering, you’re just trying different things out. And you might get back to the same handhold again and again, to kind of master that little bit as best as you can.

The ‘problems’ of co-creation are recurring, and like bouldering often require slightly different solutions and adaptations according to particular circumstances. A wide number were discussed during the workshop. Three that relate to the ethics of co-creation included:

Authorship

Co-creative works have multiple participants, but the status of those participants is fluid, with a spectrum of possibilities ranging from co-authorship to accreditation to anonymity. The artists discussed how while their own name was intrinsically associated with a piece of work, thereby authoring it, they wanted encourage a space of shared responsibility, respect, and trust; creating the conditions to learn from each other and enhancing each other’s voices and satisfaction with the work created.

Responsibility

Separate but aligned to authorship were various forms of responsibility: taking responsibility for an artwork, for participants, for stories, for communities. This was also linked to legacy and what tangible outcome or intangible memories were left behind. Several participants in our walking interviews discussed enduring personal resonances, such as Thys Hartley who spoke about the temporary artwork having long lasting impact on the market community: ‘After the event, we realised it was something the market was missing – a space to explore, talk and feel safe – so we spent months putting in applications for a similar permanent space.’

Payment

Engagement with remuneration for participants was seen as essential and needed to be explicit, recognising that money can be the reason some people can’t participate; that different people have different experiences of money; that structures and systems often mitigate against payment. Payment was recognised as complex, as potentially producing transactional relationships, as rarely being ‘enough’, as potentially reducing aspects of co-creation to how much funding there was available.

As these three examples illustrate, the decision moments in co-creative processes are subtle, with the right move in one circumstance not always the same in another. The visual metaphor of bouldering reflects this, requiring thinking and action to always be primarily lead by circumstance.

Representation 3:

Co-creation as mycelium:

Relational practice

Illustration by Alyce Wood

Co-creation is at its fundamental nature is about relationships between people, as framed through and constructed by the particularity of an arts project. In discussing audience participation in theatre, Gareth White terms this the ‘aesthetics of the invitation.’ In discussing co-creative practice, the idea of an invitation – or alternatively an ‘offer’ – was raised, with again a sense of variety about what this might be. Often works might have different options or ways in for different people, dependent on what people might desire and expect. Alice Withers noted that responses to the invitation depended not just on the offer itself but upon the personality of each individual as much as anything else.

The relationship between artists and participants was describes as one of ‘structuring participation’ (Ling Tan), facilitating other people to have power (Toni Lewis), empowering people to tell their own stories (Katie Etheridge), creating possibilities where things can happen (Alisa Oleva). The co-creative processes were therefore concerned with structuring ways of working together and while there were multiple ways in which this occurred some ideas recurred:

Place

Co-creative works were often driven by place, the artists immersing themselves in context. Artists commissioned by Compass described the importance of engaging with people face to face, making connections, and finding the ‘right’ people to work with. Katie Etheridge talked about the importance of place within her practice, especially when creating Public House: ‘Public House is about what a pub is in term of the social place. It’s working in and with places that are sort of cool, like fragile ecologies that have spaces.’ Joshua Sofaer echoed this use of space within the conversation explaining that he is ‘led by the place rather than helicoptering in.’

The importance of place was echoed in participants responses in the walking interviews, where memories were strongly located to places: ‘I have brought us to Wapentake because it is where I first met Katie and Simon, and I’m taking us to The Palace because it is where one of the most profound conversations of my life happened with them. They changed the way I view this city.’ This personal experience of place and memories was reflected in Alisa Oleva’s personal experiences which impact on her creative process, ‘because of the way my personal history is spready in different places, and my need to connect those places […] I connect people and places who may never meet in real life’.

Small is Beautiful

One aspect that several artists valued about working with Compass in particular was the permission it gave to place positive value on smallness: the value of limited production, of small audiences, and seeing inherently local networks as a virtue. This both fed into an aesthetic (a value of tiny details, the minutia of life) and into a political ethos (investing in marginalised communities and stories, resisting centring the ego of the artist). Joshua Sofaer praised Compass’ model of commissions, ‘I really appreciate Compass’s dedication to the idea of the small audience. I think it has quite a unique model. Maybe it can only happen in a city like Leeds, which is big enough for things to be able to be lost or not feel like they’re necessarily taking over everything, but also small enough that you don’t necessarily address the masses.’

Empowering the everyday

A natural synergy of working with communities as co-creative participants was to engage with their interests, their stories, anecdotes and experiences. One function of the artist in this context was to work off and with people’s obsessions, and share the things that are important to them, to empower people to tell their own stories as ‘everyone is expert of their own life’ (Katie Etheridge). Through finding out and working with what people care about, work had the potential to both galvanise engagement and forge connections for a deeper impact. It was seen as providing opportunities for people to be heard and to value the multifaceated nature of people as people.

Temporary Community

Ling Tan spoke about her previous work within architecture and how building landscapes can make temporary communities: ’it is interesting how you can bring people together who may have never met even though they live seconds away from each other. You hope they continue to speak post-project, but even if they don’t, talking to people they wouldn’t usually makes a difference.’ This awareness was echoed strongly in the conversation between Compass Festival producers, reflecting their awareness of the festival as a ‘temporary moment’ that inserts itself in the life of the city.

Failed Relationships

There can be a narrative around relational practice that fixates on the positive, and Joshua Sofaer noted it is important to get beyond the idea that ‘social practice always goes well’ and to think about moments of failure. Specific cautions included the risk of engaging in purely transactional relationships or worse the risk of ‘excavation’ (Simon Persighetti) – that is the artist mining communities for input in an exploitative manner akin to a colonial relationship that benefited the artist far more than the community.

A visual representation proposed by Toni Lewis for the nature of co-creative relationships was that of the mycelium, the underground, unseen, interconnected network of threads that link the visible fruiting body of fungi not just to each other but to trees and plants in a symbiotic relationship. For Lewis, this image captured how co-creation operated as one ‘giant ecosystem’, where we rely on each other but which is also fragile and contained the potential to do damage to each other.

Conclusion:

Co-creation or Making With

Through the course of the dialogical workshops it became clear that there was often a bifurcated relationship with co-creation. On one hand, there was a vibrant and rich engagement with processes of co-creation in practice, a desire to interrogate what was happening on the ground in terms of decision making, relationships and their consequences. At the same time however, there was caution and occasional trepidation about the term itself, which was seen as bringing with it baggage, unwanted limiters or external arbiters.

In particular there was awareness that in abstract co-creation was politically problematic for the manner in which it often promised far more than it delivered. Rhiannon Armstrong described it as often performative rather than real engagement with change: ‘co creation is language used by the powerful to give themselves permission to look away from extractive power structures, and leave unaddressed the status quo of who gatekeeps, and who has access to financial resource and platforms in the name of culture.’ While Joshua Sofaer commented: ‘I don’t use the term cocreation. The idea that the, the whatever we want to call them, community participants that are invited into a project are somehow emancipated or free or liberal or in control of the project is just not what happens.’ The term co-creation implies particular ways of working, but the term was often seen as being used in a manner that avoiding interrogating or evidencing whether that existed in on-the-ground practice.

The visual representations we present here all describe structures of interconnectedness, very much aligned to the fluidity of practice and the embracing of complexity. Such fluidity was exemplified in that recurring assertion that fundamentally ‘it depends’ – upon circumstance, funding, objectives, people, place and a whole lot more in – and the assertion of this as a positive, rigorous and responsive way of making with. As well as participants, artists also use the term making with to describe their relationship with Compass themselves, describing this in terms of a relationship of maximum flexibility to develop the work as it needs to develop. Making with as a term resists definition, it is far too everyday for that, but instead requires the explanation on each occasion of exactly what we mean and exactly what we are doing.